Natural wound healing

There are essentially two outcomes, scar formation or ulceration. The body’s response heals the wound by forming scar tissue, but when this fails, the exposed wound becomes a chronic ulcer.

The natural process of wound healing is of two types. If the wound edges are close together, healing can occur directly by growth of cells in the edges of the wound, to span across the wound itself. This process, called healing by primary intention, is results in rapid overgrowth of skin epidermis to reform the barrier layer of skin and close the wound to the outside world. Formation of scar occurs if the original wound penetrates the skin dermis.

Wound Healing by PRIMARY Intent

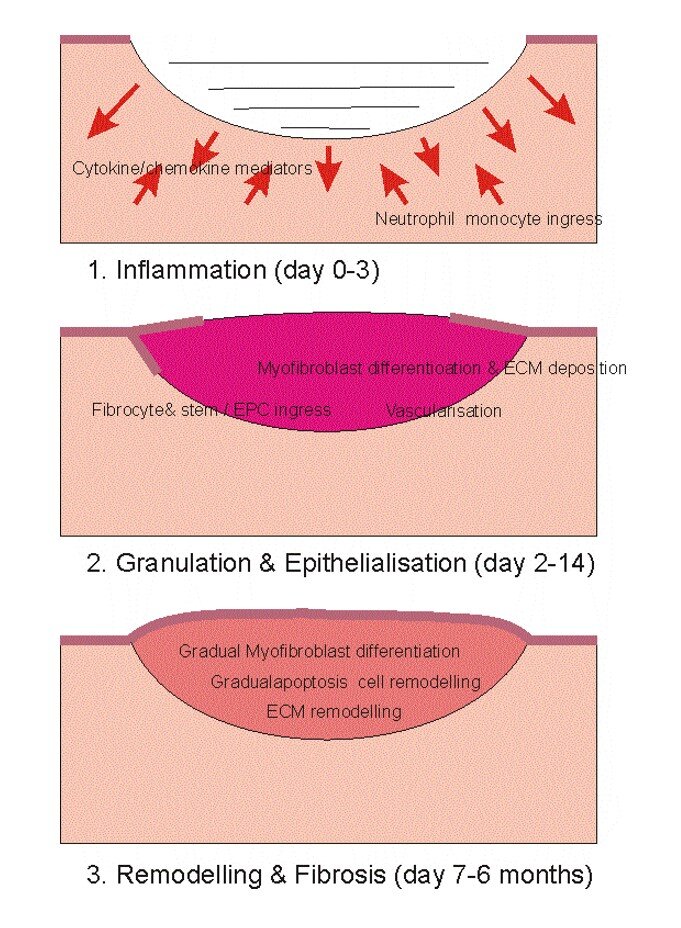

The three stages of healing occur in rapid succession.

The extent and depth of the injury determines the degree of inflammation, and cell migration into the wound space.

Importantly, the epithelium is able to grow and rapidly close over the wound to re-establish the skin barrier.

Scar tissue forms within the dermis. The extent of scarring depends on the gap between the wound edges, the depth of injury and inflammatory response.

The second type of healing occurs if the edges of the wound are separated, even by more than a few millimetres. The natural process of inflammation in response to the wound stimulates the migration of cells into the wound from the surrounding tissue. These cells pile up and form a delicate mass of tissue which gradually turns into scar tissue. As this forms, the epithelial layer of skin grows over it from the margins, to eventually close the wound. This entire process, called healing by secondary intention, can only happen effectively if the wound is protected to allow healing to occur at all. The natural protection is provided by a scab, the dried-out cells and blood clot, underneath which the healing process can occur.

WOUND HEALING BY SECOND INTENTION

For large wounds, the initial inflammatory response to skin loss triggers a vigorous migration of cells from surrounding tissue and bone marrow, into the wound.

This influx of cells builds up ‘granulation tissue’, which gradually differentiates into highly active fibroblasts, and gradually matures into fibrous scar tissue.